Words & Images: James Bird

Naples isn't a normal place. Irrationally beautiful. Immediately daunting. Really, really welcoming. Neapolitans greet you with open arms, open mouths, and open hearts. It's a place kept just about in control by being out of control. A hot city in the hot shadow of a hot volcano. A big gob full of clams, Camorra, and Catholicism. Superstitions, scugnizzi, and scooters. And Maradona.

Naples is pregnant with Diego Maradona.

Diego was elevated to the status of the Gods. A social, psychological, and physical revolutionary—over 30 years on from Napoli's first scudetto, his aura is still slaloming through tight backstreets, outside sticky bars, and around the workshops of carpenters. Here, Maradona was way more than the best footballer in the world. God. Rebel. King. Animal. Saint. Sinner. Brother. Winner. And most importantly, he was one of them. Diego Maradona married the street with the sublime and absorbed Naples as Naples absorbed him.

So, with a Dictaphone, a bunch of phone numbers, and an Italian vocabulary more Steve Stone than Rosetta Stone, I went to have a chat with the psychologists, the lads playing cards, the journalists, and the merchandise sellers for whom Diego Armando Maradona is still a big part of the air they breathe.

THE CARPENTERS

We're on the way back from lunch. Stomachs talking through pasta and bread and meat and cheese and coffee. Halfway towards the Centro Storico, I spot a Napoli flag on the wall of a dusty carpenter's workshop. There are three blokes in there, all hammering away at things and shouting at each other over the top of the wood thudthudthuds. By the time we've established that 'Io una giornalista Inglese' that is 'scritto-ing uno articolo e Diego Maradona’ there are three big bottles of Peroni and four prosciutto crudo panini nestled amongst the wood chippings on the bench. These are all good things.

Giuseppe pops open a beer with his chisel, glugs a load into some plastic cups, and pulls a poster from a cupboard of Maradona balancing a ball on his head. He points at a photo behind the tool rack of Maradona with his arms around a load of Neapolitans. Outside in the heat, and inside in the shade, Maradona appears on walls and out of cupboards as soon as you mention his name. A poltergeist.

Giuseppe refills our plastic cups and tells me about another time Maradona just appeared.

"The first time we won the scudetto, I was only seven years old, so I don't remember much. But I remember more from when we won the UEFA Cup—I remember there were fifty of us just from this family in the garage. We'd never won anything before, and then Maradona came along, and everything changed. Everything.

"When I was small I used to train on these small pitches close to the stadium with some of the kids of the Napoli players. I used to leave my family in the morning and then play there all day. One time I heard an adult behind me say 'Passa, passa', and I turn around, and it's Maradona asking me to give him the ball."

"You passed the ball to Maradona?" I say.

"Si, one time."

"Fuck."

He points at his arm and asks me in English what they are, and I say that they are goose bumps.

He gets his chisel, runs it down the raised dark hair on his arm and repeats "Si, goose bumps".

Giuseppe pops another bottle of Peroni, asks me about Brexit, and shows me a roll of toilet paper with Gonzalo Higuaín's face on it.

THE LADS AND THE LASSES PLAYING CARDS

There are a group of men and women sat at a plastic table in the middle of the road in the middle of the Quartieri Spagnoli.

"Mi scusa, posso chiederti alcune domande su Maradona?"

("Excuse me, would it be possible to ask you some questions about Maradona?")

"IL RE, IL RE!!!!"

("THE KING, THE KING!!!!")

THE MERCH SELLER...

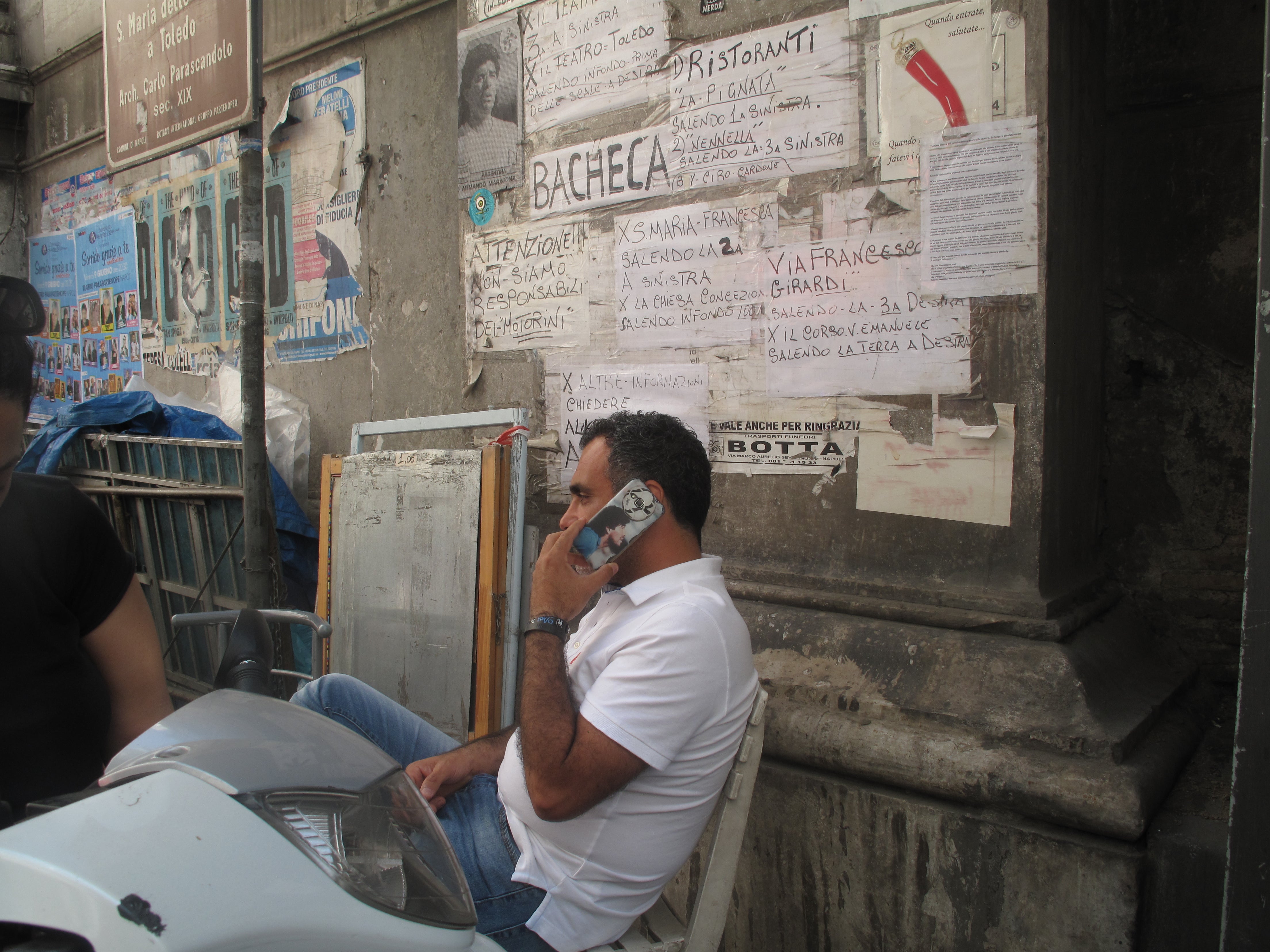

Ciro Cardone sits on his sticker-plastered scooter, parked on a corner that marries the hectic Quartieri Spagnoli to Via Toledo—a 1.2 km long street. His Napoli merchandise stall is five yards across the road: all blues and whites and flags and shirts and scarves.

He offers me a coffee, kisses me on both cheeks, and tells me that Diego Maradona was his first girlfriend.

"I remember when the transfer news came through, I was home alone and listening to the radio in my room. I turned the volume right up and went crazy. Maradona coming to Napoli was what started my passion for football. I was only a young guy, but I travelled all over Italy to follow Maradona and Napoli. I fell in love. I was in love with Maradona. I was going to the games just to watch him play. I was 12 when we won the first scudetto. He gave me more joy than I ever knew—he made us beat Milan and Inter and Juve..."

Ciro talks with his eyes behind blue-tinted sunglasses. He talks about going to Verona alongside 20,000 delirious Napoli fans without tickets. He talks about drinking, smoking, chatting, singing on the bus there, and then the bus just disappearing after the game. He talks about thousands of them getting trains all the way back down the spine of Italy while police helicopters followed them. He talks about the sheer joy, the ecstasy, the blue bliss. He talks about the iconic 3–1 win in Turin against Juve in 1986, the start of Il crollo dell'impero bianconero—the falling of the black and white empire.

That whole game is available to watch on YouTube, and the roar you can hear from the Neapolitans as Napoli come back from Michael Laudrup's third minute Juventus goal to go 2–1 up 25 minutes later isn't just the roar of people celebrating a goal, it's the roar of the Quartieri Spagnoli's scooters, the roar of the raucous South conquering the restrained North.

This was the game that gave Napoli the belief that they could do it—that the scudetto was not a classist piece of silverware reserved for the rational Milanese and the industrious Turinese, but a piece of treasure to be captured by the South.

"When Maradona was playing, it was always a party," says Ciro. "He made me feel fear, he made me feel anger, and he gave me so much adrenaline. Maradona caused emotion through expressing his rage, and therefore our rage. He was my first girlfriend."

I look over at the stall and think about how hard it was to let go of my first girlfriend, and how I'd probably have set up a merchandise stall selling T-shirts with her face on it if people would have bought them. But nobody else understood her, obviously, whereas Naples' fathers and mothers and kids and cats understand about Diego—he was a first girlfriend to many. It's not his thick thighs, luscious curls, or his flexible hips; it's his way of being. He embodied the intricacies and contradictions and beauty and carnage of the city. I'm leaning on Ciro's scooter, and I say "Grazie mille", and he kisses me on both cheeks and then says in Italian, "When my brother was one year old, I gave him a Maradona T-shirt and a captain's armband, and he still has them. Jamaica has Bob Marley, Cuba has Che Guevara, and we have Diego Maradona, Jam-ez."

I'm leaning on Ciro's scooter, and I say "Grazie mille", and he kisses me on both cheeks and then says in Italian, "When my brother was one year old, I gave him a Maradona T-shirt and a captain's armband, and he still has them. Jamaica has Bob Marley, Cuba has Che Guevara, and we have Diego Maradona, Jam-ez."

He's bloody great, Ciro is, and as me and Gisa are about to walk away he points at a man sat on a stool next to him and says "This is Antonio; he will show you the magic."

... AND THE MAN WITH THE MAGIC

I'd had lunch with Antonio Di Bonito, the co-writer of Maradonapoli, a feature-length film that was released exclusively in Naples for 11 days earlier this year, and he'd mentioned another man called Antonio that I should talk to and gave us his number.

We rang him and got no reply, but it turns out it's this one—the one sat in front of me—the one showing us the magic. Antonio slowly leads us five streets down then four streets up then two across in the Quartieri Spagnoli and opens the door to his shaded courtyard. We go up to the second floor and then across the balcony to his front door. Painted above are the initials "M10".

Antonio's wife is sitting at the table and immediately offers us a coffee, and when we decline she puts three plastic cups on the table and pours us all a cup of chilled acqua frizzante. It's fucking baking outside. We slurp them down, Antonio leaves the room, and his wife again offers us coffee—which we decline. Their two kids are promptly chucked out the house, and Antonio takes us back into the corridor outside the lounge and turns off all the lights. I genuinely have no idea what he, or we, are doing.

Antonio puts his finger to his lips, walks down the corridor and opens a door on the right. We walk in; he shuts the door, presses play on a remote control in his hand, and on a TV in front of us—like a tousled-haired genie from a lamp—appears Diego Maradona's face, complemented by Tina Turner's "Simply the Best" playing in the background. As the compilation moves forward, (Diego shuffling his hips, Diego balancing an adidas Azteca on his forehead, Diego's name appearing in WordArt blinds across the screen) Antonio turns on uplights one by one in various cabinets in time to the music. It's insane and great, and then I start to notice what's in the cabinets.

Inside one are the Puma Kings that Diego wore in the home leg of the 1988/89 UEFA Cup semifinal against Bayern Munich—gold name still etched, mud still clinging, laces still untied. Inside another is the captain's armband Diego wore in a Serie A match against Lazio in the 89/90 season. There are training shirts from '85 and balls from '87. There's blue Buitoni shirts from 1990 on mannequins, white Buitoni shirts, green V-neck Mars training sweaters, white Mars shirts, red Mars shirts, blue Mars shirts, and all with accompanying information cards. He's got the lot. And then, at the far end of the room on a clockwise rotating mannequin, is one of only two No.9 shirts Maradona ever wore. As it continues to rotate, Antonio tells me that he wore it in a Coppa Italia away match at Pisa in the 1990/91 season. Antonio is the man with the magic.

"Antonio, Grazie, grazie mille", I say.

"Niente", he says back with a proper lovely smile.

Antonio leads us back to the lounge; his wife asks us if we'd like a coffee and we walk back down the stairs to the heat and the scooters and the real world.

You know when your mom says "Ooh yes, I went into old Auntie Vera's room the other day and I could feel her presence, I really could—there was definitely something there, there was. I'm telling you, son: she was there I could just tell, and I could feel it, and it was definitely her" and you go "Yes, mom, that sure is something". Well, yeh, this is it. Maradona is not managing Al Fujairah S. C. in the United Arab Emirates First Division. Maradona is in the air. In Naples. In that room. In Antonio.

(Later that night I have a little rummage around on the internet for any info on the No.9 shirt and find an interview with Gianfranco Zola, who developed an important relationship with Maradona while playing with him at Napoli. Maradona was a huge influence on Zola ("I learned everything from Diego"—GZ), but also a massive advocate ("Napoli doesn't need to look for anyone to replace me, the team already has Zola."—DM). In the interview, Zola is asked "What's your favourite memory of Maradona?" and answers "Maradona always used to keep the No.10 shirt for himself. However, once we played an Italian Cup game in Pisa and so I went to take the No.9 shirt, but Maradona brought the No.10 shirt over to me. He told me that he wanted to wear the No.9 to pay homage to his friend Careca, saying he wanted to play once with that number, but I later found out that he gave it to me for the experience. I was very flattered. That was a great gesture. It gave me a lot of confidence." That 'great gesture' is currently spinning on a torso mannequin in that tiny hidden room in the Quartieri Spagnoli.)

THE WRITER BORN OPPOSITE STADIO SAN PAOLO

Right amongst the chaos of the Quartieri Spagnoli is the Fondazione Foqus, a beautiful 16th-century convent transformed into an urban regeneration project doing really important things for the people of the city. Set up by the Dalla Parte Dei Bambini (From the Children), a social enterprise based in Naples, there's a nursery, a library, a school for disadvantaged adults, and a really nice cafe where I meet Max Gallo from Il Napolista. Founded in 2010 by Max and Fabrizio d'Esposito, Il Napolista is an online journal of opinion focusing on football culture and Neapolitan society. Max was born in Fuorigrotta, right in front of the San Paolo, and lived there until 1991. He tells me Maradona was his first girlfriend, too.

"I remember the first Maradona flag I saw. He had his arms spread out, and his hair..." Max stands to imitate his wavy hair. "It moved in the wind like he was alive. I went to the ground every Sunday—at the time we only played on Sundays. And, in Naples, we spoke only of Maradona. He was a collective force. For me at that time, life was sensually Napoli and Maradona.

"In 1985, we beat Juventus for the first time in 12 years. Maradona scored the winner, and that is his goal—the goal of Maradona and Napoli. You know which goal I mean? The free kick in the area. It's the goal. And I was in the stadium, in Curva B. It was raining—really raining hard—and I remember looking around after the goal went in and there were adults just lay out on the wet floor in absolute bliss. It was crazy, totally crazy."

And I do know which goal he means. On YouTube, there are videos titled "PUNIZIONE DI MARADONA DENTRO L'AREA DI RIGORE" which means "THE PUNISHMENT OF MARADONA IN THE PENALTY AREA". In glorious Buitoni blue, Maradona collects the ball in the centre circle and proceeds to skip, slide, jink, and jive past five Juventus players who each try to foul him. He eventually gets hauled over in the penalty area, but it takes two Juve players to do it. Maradona is screaming and laughing, and the Juve players are sort of laughing in disbelief at each other on the grounds of his run. Inexplicably, the ref gives an indirect free kick inside the area for gioco pericoloso (dangerous play), and from about fourteen yards out and with the wall no more than seven yards away, Maradona strikes the rolling ball in a motion that involves flicking his heel backwards at the same time as caressing his foot forwards—creating enough freak backspin, curl and dip to loop into the top corner. Remember the first time you saw Ronaldo knuckleball a free kick, and you were like: what on earth was that?—this is like that, but more delicate. It's fucking divine, really. The crowd are on the pitch, the policemen are on the pitch, God is on the pitch.

"Maradona was, and is, like Muhammad Ali. A great player, great fighter—but also a political leader, and in Naples he found his favourite place. He spoke of the opposition with the North—with Turin, with Milan. He is a charismatic leader—a Braveheart, a Napoleon."

He was Neapolitan, essentially, I interject. And he says yes, yes he was.

"He was simply a magician. From a throw-in, he would always have three players around him." Max puts his beer down, stands up, and in the middle of the cafe starts to imitate Maradona receiving the ball from a throw-in with three players around him. He hits his hand against his chest to show him cushioning the ball, feints one way and then imitates the other three players looking in different directions as Maradona shimmies off with the ball. It's a Maradona dance. "Always", he says and sits back down. "Always".

"I remember another match: rabona. Rabona. Napoli are in the attack and Maradona does a rabona for a cross to Luigi Caffarelli: goal!" Max puts down his beer and stands up again, rabona-ing a cross and then turning around to head it into the back of the net. Another Maradona dance. "We are forever standing when we're in the Curva B, but not everyone is jumping and cheering in reaction to this rabona. People are frozen, surprised, shocked".

I suggest the word "petrified—turned to stone", and he says "exactly that, we'd never seen anything like that before."

"But, I have problems. Maradona is the past, a great, rich past. But I think there is a present, and there is a future. In Naples, Maradona is too present. In Il Napolista, this position of mine is not popular. I remember all of Maradona—everything about him. But we are speaking about something 20–30 years ago. It's a problem to always stay in the past. It's difficult for me to say this because I don't want to take the role of the opposition. But there has to be a future."

Max is the only person out of everyone I have spoken to who presents Maradona's immortality as a possible problem. He is deeply in love with Maradona and the effect he had on the city. But, Max acknowledges the need to move on and realises the danger of nostalgia. Nostalgia illuminates stagnancy—and although Maradona's effect on Naples is constantly moving and evolving, I get what Max is saying.

Max has a Clapton Ultras sticker in his office. Max is a cool guy.

THE KIDS IN FRONT OF THE CHURCH

It's scorching hot, and there are a bunch of kids playing football in front of a massive church with a sort of floater/sort of heavier-beach-ball type thing, using scaffolding for goalposts and graffiti for a crowd. Kinda Subbuteo, kinda Gomorrah.

Every time they score a goal they yell "Maradona! Maradona!" and every so often they yell "Scudetto! scudetto!" They're about ten years old, and this thing happened about twenty years before they were born, but Maradona is a part of their minds, and a part of their games, and a part of their lives.

THE SOCIOLOGIST

Luca Bifulco is a sociologist and teacher at the Universitŕ degli studi di Napoli Federico II, Scienze Sociali. He's written books, essays and papers titled things like The Essence and Routinisation of a Hero: Maradona for Two Generations of Neapolitan Fans, and Maradona, Naples, Italy, Argentina, Social and Identity Issues, along with Football as an Integration Tool: The Case of Afro-Naples United. Luca is very MUNDIAL, really knows his stuff, and I'm incredibly happy to have his time. He takes me for pizza, we go back to his office, and he talks to me about Diego.

"There is a bar in the centre of town that invented a note with Maradona's face on it. You would pay for the voucher and then you can use it to buy a coffee at the bar when you want one. And the story goes that that little by little, this voucher became normal money. So people started using it as normal currency to pay for goods, and people started accepting it as normal money. Crazy. The guy had to stop selling them because obviously, fake currency is illegal. This can only happen in Naples with Maradona.

"Neapolitans are full of pride, local pride. We think that Naples is different," he says. "It's full of problems, but we think that it is the best place in the world. We have the sea, we have a volcano, we have pizza, we have the music, the theatre. It is the same pride that we have with Maradona—he is a symbolic recognition of this pride. In the 80s, suddenly we have this winning team with Maradona—he nourished us.

"We are the only big city in Italy with just one professional team. So the connection between the team and the city is natural—it's automatic. There is another thing, a linguistic thing. With other big clubs in Italy, you say the name of the team and the name of the city, and it's different. You can say the name of the football fan and the name of the citizen, and it's different. With Naples, it's the same. In Italian, it's Napoli—Napoli/ Napolitano—Napolitano. In Milano, the citizen is Milanese, but the fan is Milanista. There is an automatic connection between citizen and club in common language.

"Maradona had all of the features that Neapolitans represent themselves within. He was an anarchist, a rebel. He doesn't have the order that they have in Turin, at Juventus. He was not continuous; he was unpredictable—full of the features that Neapolitans connect themselves with. He was a rebel and a genius. The Neapolitans like to do things in spite of rules, and Maradona showed to the world that you can win with these Neapolitan features. He gave us a social redemption against the arrogant North, against the rich North. He gave us a revenge. He gave people a way to be proud of their way to be."

Luca takes me to meet Bruno: the Man with the Hair, and Marco: the Figurine Maker.

THE HAIR, AND THE FIGURINE MAKER

Bruno owns a cafe in the Centro Storico with an altar that exalts Maradona. Bruno gives me coffee and tells me that the piece of Diego Maradona's hair that is encapsulated in the altar is one that he stole from the back of an aeroplane seat after a Napoli loss to Juventus. Maradona was angry and left the seat and Bruno nicked the piece of hair, showed his friend, and put it in his wallet. Then he started the altar, added some banging photos and placed ornate iconography around it. It is the Altare di Maradona, and it is in the beautiful Bar Nilo on Via Tribunali. In 1991, when Maradona left, he added a vial of blue liquid: "Napoli's tears".

He says this is a relic, a little piece of the God that has brought his cafe luck and business ever since.

Bruno says that Maradona is a part of the city and a transmission of joy. A transmission of joy that continues to the younger generation of the city and will continue to do so. He is deadly serious, deadly funny, and serves deadly coffee.

We walk up to meet Marco Ferrigno. Marco runs a terracotta figurine shop in the more touristy area off Via Tribulani. His works are considered to be amongst the best of Neapolitan terracotta and are created using the same materials and processes as they were 150 years ago. His products are mainly those of traditional Neapolitan crib iconography: vignettes of shepherds and pastors. He also makes figurines of Diego Maradona.

Marco talks to me about the euphoria of the party for the scudetto, the euphoria of the party for the UEFA Cup/ scudetto double, and about Maradona's iconographic importance.

Marco also says he always wanted to meet three people: "Sophia Loren, the Pope, and Maradona." He points at a photo of himself and a grinning man with bushy hair embracing through a car window. "I've met them all", he says with a smile made of teeth.

THE STREET ARTISTS

Sometimes, people on TV shows and on the radio and in books say things like "OH YOU MUST GO THERE, IT IS AN ASSAULT ON THE SENSES", and you think "Yes, I must go there, I like my senses to be assaulted."

Naples is one of those places that people would say this about, but it's less of an assault and more of a cocoon. It is an envelope. A womb. Naples is a wombing of the senses. You want to get away from an assault; you don't want to get away from Naples. You want to taste, smell, hear, and touch the whole lot. Maradona felt the same way. "Get into the womb, Diego, you're staying with us", they said. And he did.

San Spiga's Maradona murals grace the Quartieri Spagnoli in a way that reveals its soul. They are cool, beautiful, and important. These aren't cherries on the top or palm trees on the beach—they're physical manifestations of the Quarter's spiritual essence.

Naples is a place of such extreme complexities that nothing needs to be exaggerated. So, when I say that I'm sat at dinner (for one) and somebody sets a shit ton of fireworks off in the middle of the next street and I get up and go and look what's happening and there's a family setting them off next to one of San's murals of Maradona heading the ball in Napoli's Cirio kit—I'm really not lying. Things happen in Naples.

San, from Buenos Aires, was only five when Argentina won the World Cup in 1986, and he doesn't remember anything about the tournament except for a drawing he made of Maradona: "It was obviously a very basic one—but it was still him and it was definitely my first tribute to him. I always think that his time in Naples to me is like a dream, the images in my head have that VHS colour aesthetic."

As San grew older in Buenos Aires, that dreamy technicolour aesthetic turned into a more realistic, balanced view of Maradona: "When I was more of a teenager, 13 or 14, I loved Maradona in the same way that we love Che Guevara or that kind of hero—the more incorrect ones, and I think that many aspects of my life I was learning through Maradona's life. Maybe he's done bad things, but I prefer to see the best part—the revolutionary part, and for me, Maradona is a revolutionary. And whatever he does, the people of Naples will always love him."

San is not alone in making comparisons between Maradona and Che, and the idea of learning how to live aspects of a revolutionary life through the actions of a footballer elevates Maradona from the pitch to the sky. He was juggling the ball in the clouds and flicking it up in the streets at the same time.

"I think that street art and murals are the best way to do a tribute to Maradona. It's ephemeral; the murals get dirty, they are impulsive—they go with Maradona's way of living. I also do them in Argentina in the neighbourhood of Villa Fiorito where he grew up. It makes sense for Maradona's murals to be in the real neighbourhoods, the Quartieri Spagnoli and Villa Fiorito. That's where he's from—the streets."

San saw the iconic painted Maradona mural on the internet and read up on the artist who renovated it—Salvatore Iodice—and with that got on a flight to Naples. "Everyone told me that I should go to the Quartieri Spagnoli and I had no idea where to go. But I had my image in a bag and was walking there when I saw a man outside a shop and, I remember very well, I asked him 'Do you know where the mural of Maradona is?' and he looks at me and goes 'Yes—I did it.' It was Salvatore. It was such an insane coincidence, like, yeh, man, I didn't speak any Italian, but in that instance we just understood."

It's starting to get dark and the sky is made of terracotta. I walk into a workshop halfway up the hill in the Quartieri Spagnoli at 7pm. There's a very handsome man covered in paint standing on a stool painting a big piece of crafted wood. It is defo Salvatore.

I introduce myself as James, and his mate Mario introduces himself in perfect English. We stand around the worktable and talk.

I ask Salvatore if it could have only have been Napoli, not Barcelona, not Seville, only Napoli that Maradona had such an effect on and he says that "the supporters of Napoli are different from fans from other great clubs across the world. There is such a strong relationship between the supporters and the city, and the player and the city: it's the verve of this city's community."

And so I ask him about San Gennaro, and whether Maradona is similar in importance. San Gennaro is Naples' patron saint and protects the city from all sorts of disasters. Three times a year, the citizens of the city gather to witness "The Miracle of San Gennaro" as a bishop 'liquefies' a sample of what is said to be San Gennaro's solidified blood inside a sealed glass ampoule. The announcement of the liquefaction is greeted with a 21-gun salute and lots of very relieved citizens. He's a pretty big deal. When the blood failed to become liquid in 1939 World War II had a pop, and in 1980, when the red stuff again stayed solid, there was an earthquake in nearby Irpinia that killed 3,000 people.

Salvatore says that you do not fuck with San Gennaro.

"San Gennaro protects the city, from Vesuvius, from natural disasters, from economic disasters. Maradona is a different saint—one of redemption, of success. He has always been fighting for the masses, for the disadvantaged. Maradona might be regarded as a meeting between this high religious culture and the kids playing football on the street."

Salvatore was 12 when they won the first scudetto, and he remembers people coming together and making decorations for the celebration a long time before Napoli had even won it.

"They believed in their God. I could see the spirit and the cooperation, the people of Naples are sometimes distrustful towards each other—but this was a real chance to unite and to express the community and the belonging. And, when Napoli actually went on to win it, this togetherness was manifested in the decorations."

I ask him if the mural, which was only made possible through crowdfunding from people in the neighbourhood so that he could rent the elevated platform buy the paint, is the right way to tribute Maradona, as opposed to an artwork in, say, a museum.

"Maradona is relevant in both the museum and on the street. He is the kind of icon created in a religious way—the kind of icon that creates a church. Coming back to the idea of community and sense of belonging created by the win of the first scudetto, he is a symbol of people being people together." I ask Salvatore what, removing the sociological and psychological analysis, it was like to simply watch Diego Maradona at the San Paolo. He looks at me and says:

I ask Salvatore what, removing the sociological and psychological analysis, it was like to simply watch Diego Maradona at the San Paolo. He looks at me and says:

"It was life. It was a magical experience that struck my boyhood to watch him at the San Paolo. Magic."

FRANCESCO DE LUCA

Francesco de Luca is the head of sports at Il Mattino—the Neapolitan daily paper. We meet Francesco at Caffe Gambrinus, one of the oldest cafes in the city. He's enigmatic and speaks with immense knowledge and complexity about Maradona, the city of Naples, and journalism. But, amongst all of his enlightening observations, the most startling thing about Francesco is the way his eyes jump to a sparkle when he talks about his favourite Maradona goal.

"The volley against Verona. It was just, it was simply fantastic. Fantastic."

Get the goal up on YouTube, watch the nonchalance of Maradona's technique, and feel your eyes jump too. It's fucking insane.

THE SHOP OWNER

I walk into a shop on Via Toledo that sells Levi's jackets, alarm clocks, and about 50 different types of Maradona shirts. It's got all the bits, this place.

I ask Eugenio (the owner), his friend, and his daughter if they can speak English but none of them can. I say no problem, thanks, Buon giornato. And they then say Aspetta, aspetta: wait, wait. His daughter gets her phone out and calls a man called Massimo. Within two minutes Massimo has zoomed right up to the door, parked his scooter on the pavement outside the shop, and said: "Hi James, they said you needed someone who could speak English?" Five minutes after that, another man, dressed in white shirt and black tie, pulls up outside the shop on a scooter. He brings inside three espressos in plastic cups with foil carefully placed over the top, and one in a glass cup with foil, all inside a Tupperware box. Eugenio pulls out a spare plastic cup from somewhere and delicately pours a quarter of each espresso into it and hands it to me.

"Un cafe per te."

"Grazie mille, Eugenio."

"The party when we won the scudetto was like nothing you have ever seen before, and something nobody will ever see again. For sport, commerce and the mind—Maradona came and changed everything."

Grazie mille, Eugenio.

THE TAXI DRIVER

The journalist Franco Esposito put me in touch with Armando Aubry, Il tassista di riferimento del Calcio Napoli negli anni addietro—"the taxi driver for Napoli Football over the years." That's how he's known: Armando drove Maradona and his family around Naples throughout their time in the city.

Armando meets us in the very chic Chiaia area of Naples: south and west of the Quartieri Spagnoli but north of the sea.

"The first time I drove Maradona I received a phone call on a Sunday night from Paolo Marino, the general director at Napoli," he says. "Paolo asked me to pick Maradona up the next morning and drive him up to Rome for a TV show by Raffaella Carŕ. I arrived at 8.55am the next morning, and Maradona and his girlfriend come down at 9.30am. We set off, but the journey was incredibly slow because of a huge snowstorm across the country. I was very stressed, but Maradona and his girlfriend were just sleeping in the back. My adrenaline was at a 1000%, and I was hoping they'd ask us to turn back. I had Diego Maradona asleep in the back of my car. But we didn't turn back, and I got them there on time in the end.

"On the way back the weather got better, and we stopped along the motorway at an Autogrill for food. It was almost impossible to eat because of a constant stream of adoration and fans asking for autographs. Thank goodness mobile phones didn't exist!

"As we got closer to home, Diego asked me, completely unprompted, if I had a wife and children, and signed two portraits for the kids. He was a man of the people—the people's person, and he loved the people. He trusted me with himself, and with his family members.

"I never spoke about work at home, never told my wife who I was driving. But I remember getting home one day and my wife being very shocked to say that Diego Maradona had called and was asking for me."

ANTONIO DI BONITO

We're out for lunch with Antonio, mentioned previously with regards to his film Maradonapoli, and he looks at me and says "Trust me, he's in here too."

Antonio points at the table between Table 9 and Table 11.

Table 10 is Table Maradona.

FRANCO ESPOSITO

I have been in contact with Sig. Esposito over email for the last few weeks. Esposito was head of Il Mattino—the daily Naples newspaper—at the time of the Maradona transfer and throughout his time in the city. He is the guy. To the seven interview questions I sent him, he replied with 23 pages of incredible insights into the transfer, the man, and the experience of Diego Maradona. I cannot do the whole thing justice, so here's a touch of it:

"Naples is alone and very particular: unparalleled in its contradictions and in its excesses. Exaggeration is everywhere—in its enthusiasm and in its depression—in sport, in football and in its everyday life. It is special. It is different here, and not reproducible anywhere in the world. It's an inexhaustible theatre, representing in twenty-four hours what most places represent in 365 days. Naples has one faith—soccer: it eats soccer, it feeds off soccer. Its games don't end in the 90th minute: they last from Monday to Sunday—there is no resolution to its continuity. Naples is the city of football, and it became more measurable, more obvious, more resounding and intrusive when Diego Maradona arrived.

"The fact that he came here is incredible. It is a novel or a film directed by a hidden director with a script and a screenplay that was beyond belief. He was formidably enriching for me as a journalist—not only in the aspect of the way he played football but as a human: in his irrepressible, extraordinary desire to live life to the way that he must live it. In this respect, he is an animal, a footballer of the sublime. He is the number one and the best of all time.

"The footballer Maradona has sown treasures of emotions and riches of visions here, and to Naples he has left a casket of immeasurable sizes. Naples lives in this sense of memories. This nostalgia is constantly present in the vision of the football ideal that Maradona delivered to this city. Naples has a strong, eternal gratitude to him—Diego changed the sporting and social history of this place."

***

Naples is not a normal place, and when Diego Armando Maradona arrived in 1984, they found their abnormal person. A political revolutionary, a saint of redemption or just simply a fucking incredible footballer, the open-armed Neapolitans cradled the open heart of Maradona and in return received the kind of glory usually reserved for the world of fiction. The world of sport has never seen a city exalt a person in the way the people of Naples exalted Maradona, and amongst hidden museums, packed out restaurants, and street games of headers and volleys, they continue to do so today. They aren't clinging on to his legacy; they're building on it.

Maradona is still here, in Naples, now.

This piece was originally published as our Issue 10 cover story.

4 comments

A fitting tribute to the most amazing city, well done James Bird

This piece made me start following Mundial and James. Read it again just now and was blown away just like the first time. If our planet ever dies this should somehow be preserved for a new civilization.

Goosebumps. I am a little jealous of this experience and of James Bird’s brilliant writing ability

Leave a comment